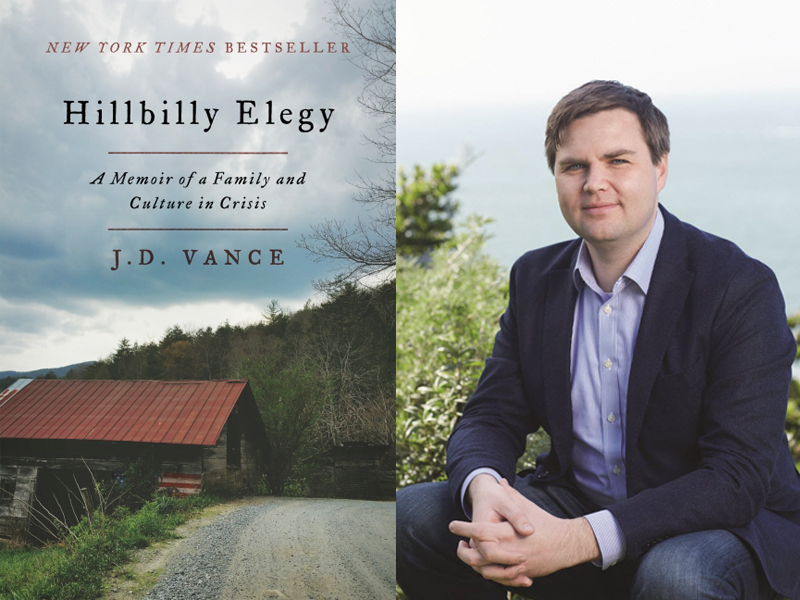

This new release initially caught my attention from an article that explains why the working-class white demographic is so ardently pro-Trump. The argument: this group feels completely left out of an increasingly ethnic, urban, and educated America. Trump’s promise to “Make America Great Again” is the first in decades to offer anything to a largely marginalized group.

J. D. Vance is a principal at Mithril Capital in Silicon Valley, previously a biotech executive, and a Yale Law graduate. But his success veils a surprising upbringing. He comes from the “hillbilly country” of Jackson, Kentucky, and his life is a series of lucky breaks and unusual circumstances that allow him to break free from the fate of his demographic. His people are one of the only groups whose children are predicted to be poorer than their parents, a group increasingly succumbing to drug addiction, alcohol, broken families, and welfare.

Hillbilly Elegy starts by nobly describing the white Irish-Scotting working class in Appalachia America. They are a people who, yes, are poor, but have their own set of deeply rooted values.

They are a people who see Family Honor as paramount. Mamaw’s(Hillbilly for grandma) brother once heard a boy joke that he’d “eat her panties any day.” Her brother goes home, pulls a pair from her dresser, comes back and orders the boy at knifepoint to eat the panties whole or he’d kill him.

There’s also emphasis on Family Closeness. Suburban Americans seemingly live so far apart and keep very separate households between generations and extended family. Vance’s family is more like that of foreigners, where the whole extended family often moves together, with a fluid boundary between the households of grandparents, parents, cousins, aunts, and uncles.

A great source of their pride is in their Love of Country. During World War One, Vance’s hometown is the only county in the entire United States to fill its draft quota entirely with volunteers. In World War Two, his Papaw leaves home to fight the Japanese in the Pacific, and his Mamaw always says with pride that “they did their part”.

They also love guns and are very comfortable with them. Once, during a road trip, his “Aunt Wee decided comb her hair and brush her teeth and thus spent more time in the ladies’ room than Papaw thought reasonable. He kicked open the door holding a loaded revolver, like some character in a Liam Neeson movie. He was sure, he explained, that she was being raped by some pervert.”

As he waxes poetic over these noble values, Vance also feels a deep shame over the seemingly inevitable decline of his people. His own life is deeply affected by an unstable mother who alternates between rehab and bringing a new man into their home. Vance would never have made it if not for his Mamaw offering a stable alternative household apart from his mother’s. Much of the novel is a tribute to his Mamaw who spent the remainder of her life providing her grandchildren with what she failed to provide for her own children.

As a first generation Asian American with immigrant Chinese parents, I imagine myself far removed from this white working-class. To me, race in America has largely been in terms of white and non-white, where Asians, Latinos, Blacks, etc. all fall into this other category. Vance’s memoir is the first time I see white as non-white just the same. The suburban middle-class whites of Ohio snub their noses as Vance’s family moves in, the same way you’d expect them to treat minorities.

By the end of the memoir, Vance engenders from me more than just sympathy, but rather a surprising amount of empathy. I somehow feel an insider with this group that I’d previously assumed was the furthest from me culturally. I go from thinking little of uneducated, gun-wielding rural whites, to somehow rooting and laughing for Vance’s Mamaw as she draws a shotgun on the suburban mailman and threatens him to “get off my fucking lawn.” Vance remembers these idiosyncrasies with the same laughing-pride that I feel for my the peculiarities of my immigrant family. Like my aunt who never stops threatening to kill and cook her daughter’s dog, who lives a more expensive life than she did back in China.

My empathy for Vance deepens as the memoir transforms into a tale of awkward upward class mobility. When big firms begin to recruit him from Yale Law, he describes the banquet dinner as class tourism, posh beyond his comprehension, literally. Soon after sitting down, he quickly rushed to the restroom to call a fellow Yale student asking what the heck to do with the 11 different utensils arranged around his plate. With working immigrant parents, I also grew up in a low-spending household. And just the same, I remember the awe as I experienced tech interviews that paid for accomodations and meals more luxurious than I’d ever seen or imagined.

Hillbilly Elegy is a simply told origin story, lacking literary flourish and thus inviting the reader to trust in the storyteller’s honesty. He tells it like it is, not caring to censor the curses, violence, or lewd jokes that define and color his upbringing. J. D. Vance’s memoir ebbs and flows with moments sometimes hilarious, sometimes somber, and works to wholesomely explain who his people are.

Disclaimer: The links above bring you to Amazon products that if purchased, help support this blog.